Published by Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Medusa: A Video Game Designed to Affect Empathy and Rape Myth Acceptance Levels.

Scroll ↓

Watch the Medusa trailer below

The Medusa trailer was designed, created and published by Alexis Boyle.

Medusa is a 2-dimensional, pixelated, role playing game with a top down view, that was created in Unity with the purpose of raising awareness and active consideration of rape culture.

Within this game players are able to take the role of both Perseus and Medusa in an interactive retelling of Medusa’s story.

The dev team combined a specific balance of disciplines and focuses from psychology, philosophy, and game design to have our game successfully raise awareness about rape culture while being sensitive and ethical in both respect to the players and their potential triggers and the sensitivity of the topic and its representation.

In this project I took on 3 major roles:

Head Researcher

As head researcher, I was in charge of designing the research study and ensuring it was completed on time and with quality. As I was the only individual with psychology experience on the team, I took initiative on all portions of the study and mentored other team members who were interested but not yet experienced with research.

Narrative Game Designer

The roles within the team consisted of 2 artists, 1 programmer and me - the designer. In this project I focused on how to design the video game with a blend of focus on the research questions for the psychology study and the enjoyability of the game itself. This role included a lot of narrative design to portray the unique stories of Perseus and Medusa in an effective way.

Producer

I also acted as the producer for Medusa! I built and maintained the project plans, schedules and roadmaps, acted as direct spokesperson for the project with our stakeholder group, organized and ran team meetings, playtesting sessions, feedback session, etc. while keeping track of action items and decisions to task out and keep track of to maintain MVP goals for specified deadlines.

Head Researcher

Overview:

Designed the overall Medusa project and project goals

Conducted background research and found reliable peer-reviewed sources for the team to study

Drafted all forms and documents to gain IRB approval for the study, includuing any edits or adjusments needed.

Designed the playtesting feedback surveys as well as the final project survey

Recruited participants for all research points

Performed all data analytics for the project (both qualitative and quantitative)

Translated all analyzed data into visual representative mediums such as charts ands graphs

Created the final project presentation including the study design and findings

Presented the project presentation to the university

Wrote sections of the final report and both reviewed and edited the report

Mentored and taught team members who had no prior psychology experience

As Head Researcher of this project I…

Research Question:

Will playing the full game “Medusa” lead to more increased empathy towards Medusa and more significant reductions in rape myth acceptance and hostile sexism than playing the shortened version of “Medusa” will?

See Details

Study of the Effects Playing Medusa had on Empathy, Rape Myth Acceptance Levels and Hostile Sexism

The purpose of this study was to determine whether a game designed to spread awareness on the detrimental effects of sexual violence could affect the level of empathy felt towards characters in the game and the level of rape myth acceptance. We hypothesized that the players who played the full game - and thus have seen the story from both the perspective of the victim and the victor - would have (1) higher levels of empathy towards Medusa, (2) lower rape myth acceptance levels, and (3) lower hostile sexism levels than players who played half the game through only one character.

Final Presentation

The final presentation provides an overview of the project including methods, dependent variables, and findings.

More Details:

Method

Participants

Participants in this study were recruited from various means such as through a private institution’s psychology study hub, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, and by email invitation. All participants took part in the study voluntarily and willingly gave their consent. In total, 73 participants took part in the study. Of the participants, 18 identified as male, 25 identified as female, two identified as non-binary, one identified as other and one chose to not report their gender identification. Ages of the participants ranged from 18 to 60 years old. Of the total participants, 27 responses were removed from data analysis: 22 did not finish the study, three did not provide consent and were not allowed to continue the study, one did not pass the manipulation check (suggesting they did not play the game), and the last removed response was a significant outlier (this individual was outside of the third quartile of the data) on multiple scales of the study.

Materials

Game Play Conditions.

We wanted to examine whether playing through a flashback to Medusa’s life before she was cursed would influence participants’ level of empathy towards Medusa and their level of rape myth acceptance. Therefore, half of the participants were randomly assigned to play the full version of the game that had the flashback and half were randomly assigned to play a shortened version of the game that did not have the flashback.

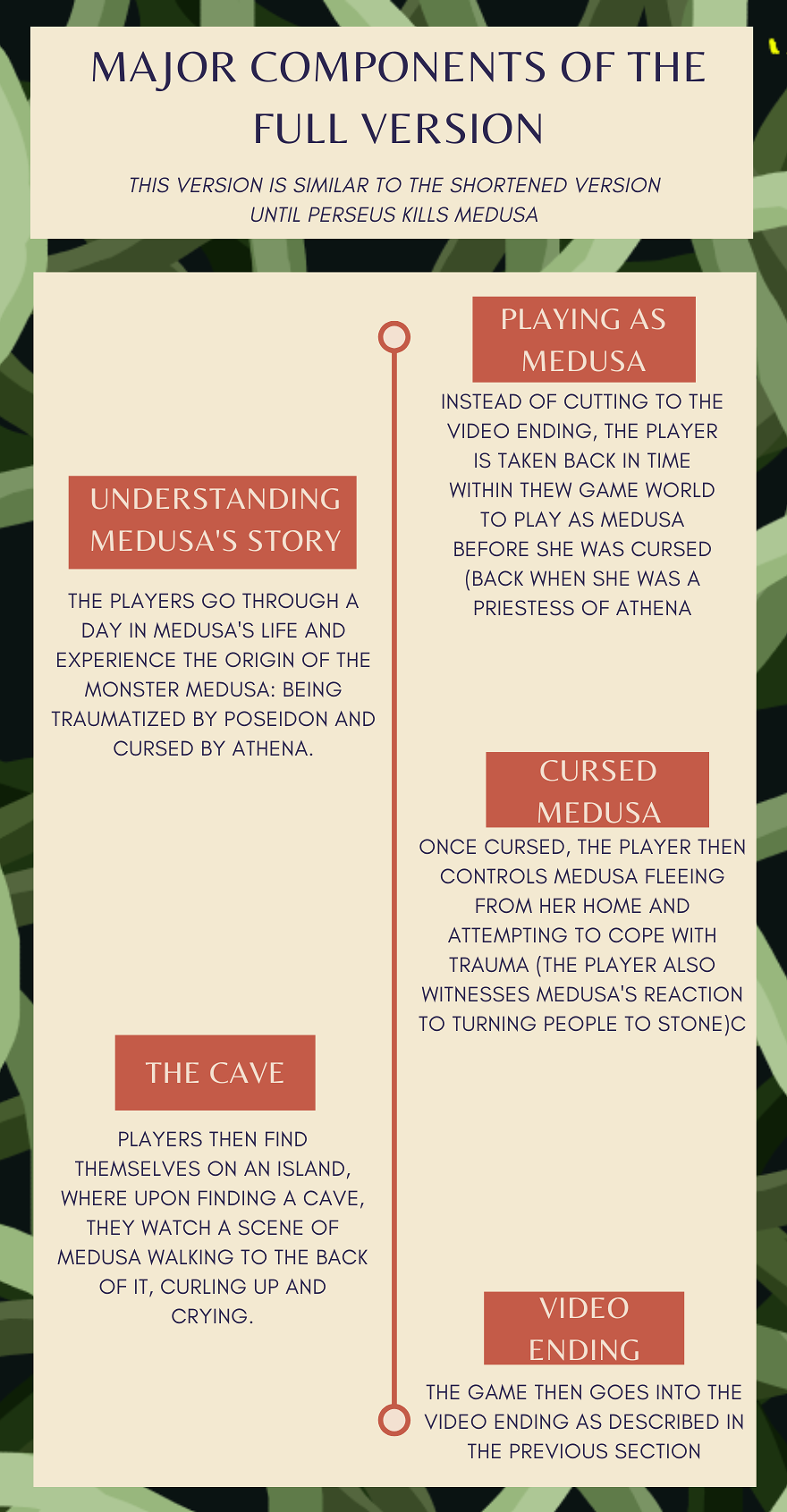

Full Game.

The executable containing the full version of the game has players go through the game as Perseus and as Medusa. This allows the participants to experience the story of Medusa through her perspective. The main points of this game version can be seen in the figure to the left.

This version of the game was meant to garner more empathy for Medusa, allowing players to witness her story through her eyes after having already killed her and having been given one side of the story. The purpose of the newspaper ending was to tie the themes of our story back into the real world, connecting to story of Medusa to modern-day sexual assault cases.

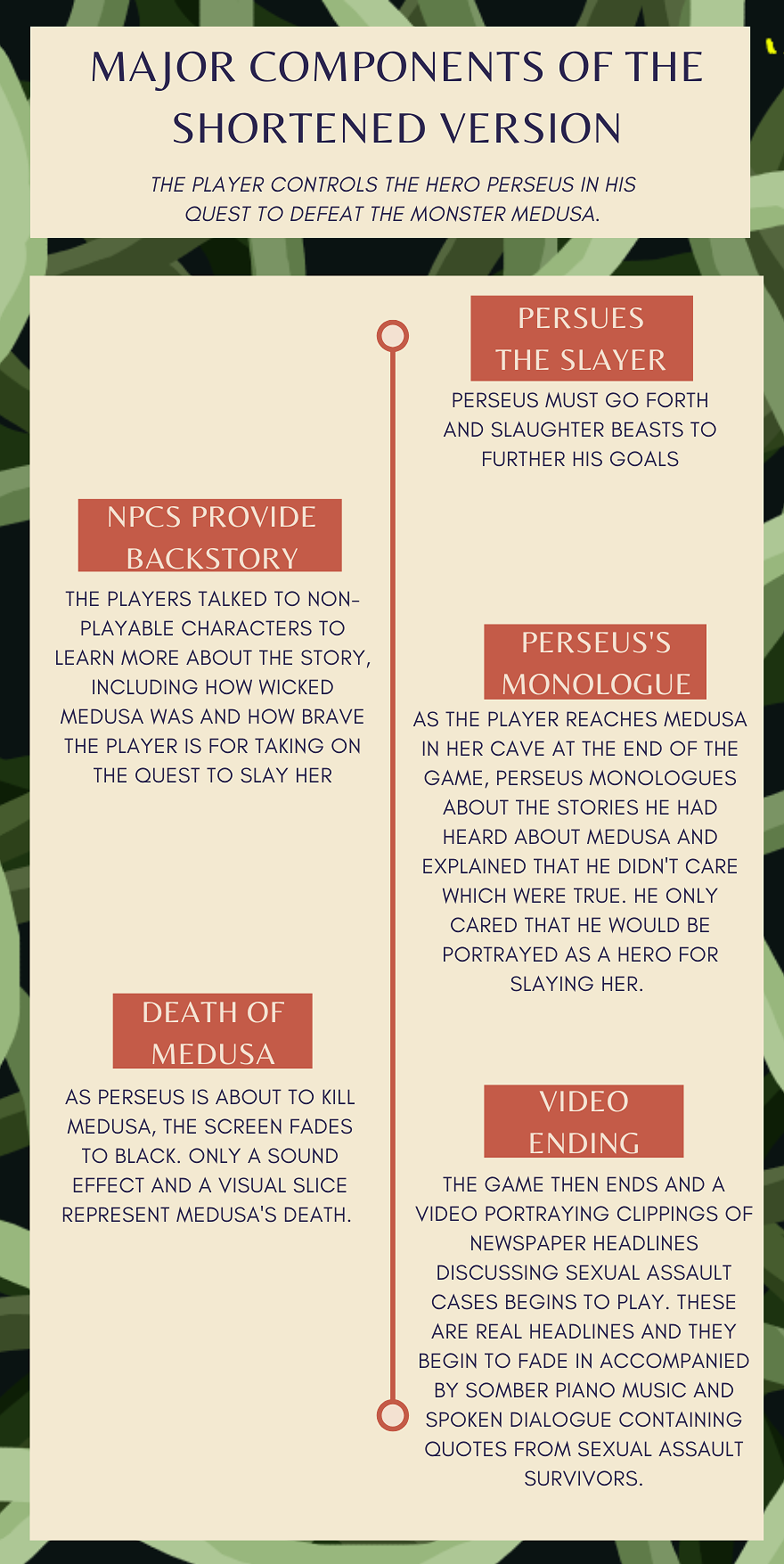

Shortened Version (Perseus-Only).

The executable containing the shortened version of the game has players go through the game as Perseus, not providing them the opportunity to play as Medusa through her storyline. The main points of this game version can be seen in the figure to the right.

This version of the game represented a typical role-playing game in which the hero has to go and slay other beings for the sake of accomplishing a task. In this version, players never experienced the story of Medusa through her eyes, only through the account of Perseus.

Measures & Findings

Manipulation Checks.

Each video game version had its own manipulation check which asked what the last event in the video game was. This manipulation check was presented with the answer format of a 4-choice multiple choice question. As the two game versions had different endings (the full game ending after the player plays as Medusa while the shortened version ending after the player plays as Perseus), the answer choices for the questions were different but the format of the questions were the same. Each had three incorrect choices that were obvious to participants who played the game (e.g., “Medusa went skydiving”). There were answer options which referred to Medusa but were not accurate to the story such as the example mentioned. These were put in place to ensure that the context clues of the study (such as the name of the game file) did not make the correct answer too obvious to any individual who had not participated in the video game. These questions were implemented to act as confirmation that the participant did play the game, as not completing or paying attention to the game, would affect their data in such a way that it would not be representative of an active play session.

Video Game Feedback Questionnaire.

Immediately after completing the game, all participants completed a survey regarding the fundamental design of the video game. There were two versions of the feedback form: the original, and a shortened version modified to follow the shortened version of the game.

-

The full version had 17 questions:

12 questions on a 7-point Likert scale assessing how entertaining the game was, how easy to understand the story was, and what it was like to play as Perseus (e.g., “How engaging was your experience playing this video game?”).

4 open-ended questions ascertaining the players’ understanding and critique of the video game (e.g., “Please explain the game’s story in your own words.”).

1 multiple choice question asking if the players had been exposed to any previous version of the game (e.g., “Have you been exposed to any previous drafts of this video game including Alphafest testing or the paper prototype edition?”).

These questions were asked to allow the team to gather feedback and critique concerning which contents of the game were efficient and which needed more improvement. The final question was asked so that during analysis, the researchers would be able to know if a participant has already been exposed to the themes and purpose of this video game, something that has the possibility of strongly influencing the participant’s opinions of the game as well as how the game has affected them (if at all). -

The shortened version of the game survey consisted of only 9 questions, broken down as follows:

4 questions on a 7-point Likert scale assessing how entertaining the game was, how easy to understand the story was, and what it was like to play as Perseus (e.g., “How engaging was your experience playing this video game?”).

4 open-ended questions ascertaining the players’ understanding and critique of the video game (e.g., “Please explain the game’s story in your own words.”).

1 multiple choice question asking if the players had been exposed to any previous version of the game (e.g., “Have you been exposed to any previous drafts of this video game including Alphafest testing or the paper prototype edition?”).

The reduced number of Likert-scale questions was due to this version of the game not featuring Medusa as a playable character, so any questions about the experience of playing as her were removed so as to not reveal the control and experimental group factors to the participant. The rest of the questions still allowed researchers to gather the same basic information about the game without sharing that Medusa was playable in one version but not the other. All of the feedback questions used can be found in Appendix C of the report.

Empathy Towards Characters Within The Video Game

After completing the video game feedback form, participants completed Batson’s Empathy Scale. This scale was modified to measure empathy experienced towards Perseus, and empathy towards Medusa. The scale included 6 items on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all; 7 = Extremely). The items were related to the 6 empathetic emotions that reflect empathy, including “sympathetic”, “moved”, “compassionate”, “tender”, “warm”, and “softhearted” (Batson et al., 1987). The 6 items were made to be specific to either Perseus or Medusa (i.e., “How sympathetic do you feel towards Medusa?”). Items were averaged together with higher numbers indicating greater empathy felt towards a specific character.

Player Identification With Characters

After participants filled out the Batson’s Empathy Scale referring to a specific character, they were shown and asked to complete a character-specific version of the Player Identification (PI) Scale (Van Looy et al., 2012). This was done for each character (Medusa and Perseus) in order to measure the levels in which the participants identified with each of the characters they have played as. The scale included 17 5-point Likert items ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The items corresponded with 3 different subscales: Game Identification (GI), Embodied Presence (EP), and Wishful Identification (WI). All seventeen items related to the subscales of embodied presence as well as wishful identification, such as “When I am playing, it feels as if I am Perseus” and “When I am playing, it feels as if I am Medusa”. Ten of the seventeen items also related to game identification, such as “In the game, it is as if I become one with Perseus” and “In the game it is as if I become one with Medusa”. There were 10 items removed from the original scale in our study due to irrelevance. These items are related to group identification within massively multiplayer online video games such as World of Warcraft. These items asked questions such as “The members of my guild are important to me” and “I regularly go online to meet with others from my guild”. Items were reverse scored as needed. Items were then averaged together with higher numbers indicating greater empathy felt towards a specific character.

Individual Differences in Empathy & Perspective Taking.

Research shows that some people are more inclined to have empathetic concern or to perspective-take than others (Davis, 1983). Therefore, after completing the PI Scale, participants completed the empathetic concern and perspective taking subscales from the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI; Davis, 1983). The items were on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = Does not describe me well; 7 = Describes me very well). Seven items were related to empathetic concerns, such as “I often have tender, concerned feelings for people less fortunate than me”. Another seven items were related to perspective taking, such as “Before criticizing somebody, I try to imagine how I would feel if I were in their place”. Items were reverse scored as needed. Items related to empathetic concern were averaged together with higher numbers indicating more empathetic concern. Items related to perspective taking were averaged together with higher numbers indicating a greater inclination to take another person’s perspective. We also conducted a median split to determine participants who were high in empathetic concern and perspective taking and those who were low in these characteristics. This allowed us to analyze whether individuals who were high or low in empathetic concern and/or perspective taking experienced the game differently.

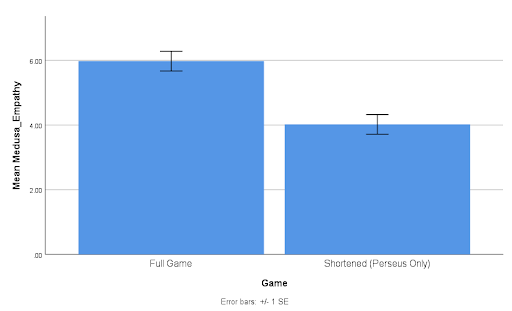

The game version played statistically significantly influenced empathy towards Medusa, such that when participants played the full version including as Medusa (M = 5.97; SD = 1.43) they reported more empathy towards Medusa than those who played the shortened version just as Perseus (M = 4.02; SD = 1.49), F(1,44)= 20.43, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.32, two-tailed test (see figure above).

This supports our original hypothesis that participants who played the full game would have higher levels of empathy for Medusa than participants who played the shortened (Perseus-only) version. This suggests that participants who were presented the opportunity to take Medusa’s perspective and play through her story as the main character of said story were able to empathize with Medusa more so than players who were not given that opportunity (depicted in Figure 19 below). This aligns with previously discussed research which focuses on empathy and player identification between them and their avatar. Further research performed on understanding and utilizing this connection may allow for technology which provides the user with an opportunity to learn from and experience significant events through interactive media.

Rape Myth Acceptance Scale.

After completing the IRI, participants are then led to believe that we were interested in attitudes towards larger societal issues. Participants then completed the Rape Myth Acceptance Scale (RMA; Fox & Potocki, 2016) which is a survey examining perceptions of rape using 14 Likert scale questions with a response scale ranging 1 - 7 (1 being strongly disagree and 7 being strongly agree). The participant responded by rating how much they agreed or disagreed with rape myths statements such as “The majority of rape claims are false.” and “Women who dress or behave in a sexually provocative manner are asking for it.”.

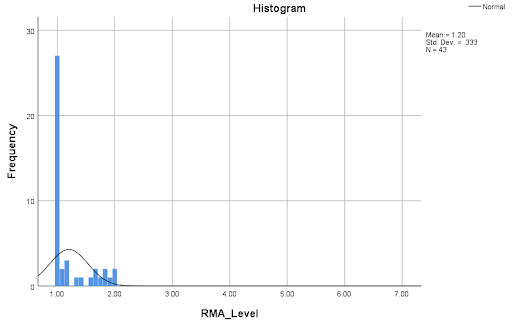

Contrary to our hypothesis, the game version played was not found to have statistically significantly influenced the participants’ rape myth acceptance levels F(1,41)= 0.49, p = 0.49, η2p= 0.01, two-tailed test.

Participants who played the full game did not show signs of decreased rape myth acceptance levels compared to those who played the shortened game. This may have been due to factors of the study and the game design. One factor that was considered was the addition and implementation of the ending video within the video game. It should be noted that there was not a high range of variation in the participant’s rape myth acceptance levels (the lowest score being 1.00 and the highest score being 2.00 on a scale of 1 to 7) as seen in the figure above. The design and message portrayed by the ending video may have provided an element of social acceptability bias (participants may have felt social pressure to report answers they felt better aligned with what they should report rather than providing how they truly feel) within our results. This is hypothesized due to the video portraying rape as damaging and immoral, which may have persuaded individuals participating in the study to provide answers to the rape myth acceptance scale which align more with the video than their own beliefs. Perhaps another study performed with more intentional neutrality would have provided a higher variety of answers, and therefore different results.

Ambivalent Sexism Inventory.

After completing the RMA scale, participants completed the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI; Glick & Fiske, 1996). The 22 items were on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly Disagree; 7 = Strongly Agree). Eleven items were related to benevolent sexism, such as “Women should be cherished and protected by men''. Eleven items were related to hostile sexism, such as “Women seek to gain power by getting control over men”. Items were reverse scored as needed, and all items can be reviewed below in Appendix C. Items related to benevolent sexism were averaged together with higher numbers indicating higher levels of benevolent sexism. Items related to hostile sexism were averaged together with higher numbers indicating higher levels of hostile sexism. In addition, all items were averaged together to create an index of overall sexism. We also conducted a median split to determine participants who were high in benevolent and hostile sexism and those who were low in these characteristics. This allowed us to analyze whether individuals who were high or low in overall, benevolent and/or hostile sexism experienced the game differently.

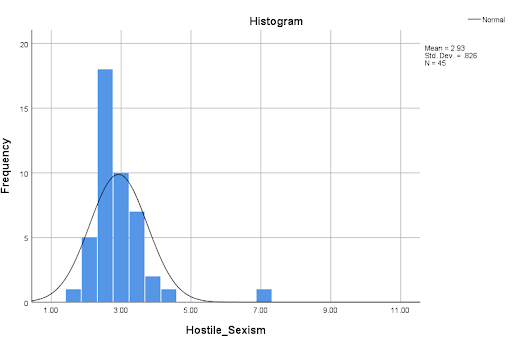

The game version played was not found to have influenced the participants' hostile sexism levels in a statistically significant way F(1,43)= 1.67, p = 0.20, N2p= 0.037, two-tailed test.

This finding did not support our initial hypothesis that participants who played the full version of Medusa would have lower levels of hostile sexism than those who played the shortened version. Similar to the range of responses found in the rape myth acceptance levels, the responses to the hostile sexism subscale of the ambivalent sexism scale were also not found to have a large variance as can be seen in Figure 21 below (minimum potential response 1, maximum potential response 11). Due to the main topic of the study focusing on sexual assault of a woman and awareness of rape culture, there may also have been an element of social acceptability bias within these results. With this being said, there is a slightly larger variety of responses with the maximum response being a 7 (although this response is noted to be an outlier). The team believes the difference between the variance in responses to the hostile sexism scale and the rape myth acceptance scale may be in relation to the direct message of the video game and ending video focusing on rape. This focus on rape may have caused a stronger social acceptability bias concerning the rape myth acceptance reportings than it did in relation to the hostile sexism reportings..

Demographics & Follow-Up Questions.

After answering all the questions regarding the game, characters, and societal issues, participants then provided demographic information. Six questions asked about their age (e.g., “What is your current age?”), student status (e.g., “Are you currently attending school as a student?” and if yes, “What is your current year?”), race identification (e.g., “Choose one or more race/ethnicity that you consider yourself to be.”), gender identification (e.g., “How do you currently identify?”), and political identification (e.g, “Here is a 7-point scale on which the political views that people might hold are arranged from extremely liberal (left) to extremely conservative (right). Where would you place yourself on this scale?”). They were also asked if they or someone they knew has been a victim of sexual aggression (e.g., “Have you (or anyone you know) been a victim of sexual aggression?”). After filling this page out, the participant was sent to a debriefing document on the last page of the survey. Once this page had been submitted, the participant had fully completed the study.

Procedures

The participants started out by opening the link to the Qualtrics survey that held all of the study materials and then began the entirely online study (we did not interact with the participant in any way). The first page of the Qualtrics survey was the informed consent page. After giving informed consent, participants downloaded the video game file, with instructions on how to do so in case they were needed. This was where we manipulated which game participants played, as half the participants downloaded the shortened version of the game, and the other half downloaded the full version of the game. After completing the game, participants were directed to an online survey to provide feedback on their experience playing the game. Participants first provided general information on their perceptions of the game itself. Then participants completed assessments of their perceptions of Perseus and Medusa. In particular, we measured empathy felt towards each character using an empathy measure developed by Batson and colleagues (1987). We also measured identification towards the two main characters of the video game (PI scale; Van Looy et al., 2012). After completing their perceptions of the game, participants were led to believe we were interested in their attitudes towards different societal issues and completed a few scales that measured attitudes towards empathic concern, perspective taking (IRI; Davis, 1983), and rape myth acceptance (Fox & Potocki, 2016) along with ambivalent sexism (Glick & Fiske, 1996). Finally, participants provided demographic information including identified gender, age, and if they or anyone they know have been exposed to any non consensual sexual activity. Participants were then thanked and debriefed as well as provided information to contact Worcester Polytechnic Institute’s Student Development Counseling Center if they wanted to.

Hide Head Researcher Details

Narrative Game Designer

Overview:

Designed the entire narrative and storyline of the game

Wrote all branching paths, dialogue and player choices

Constructed character background and relevant side characters

Found and created all audio included for the game with proper accreditation

Ran playtests and created actionable steps for adjusting the game based on feedback

Worked with other disciplines throughout production to ensure a common goal

Wrote and maintained all documentation including GDD, narrative documents, and visual mockups

As Game Designer of this project I…

See Details

Narrative Game Design of Medusa

The first thing I worked on was nailing down the concept of our game with the team and our advisors. We ended up coming up with Medusa as it is now! This presentation below shows a quick overview of our themes, ideas, reseach and design.

After discussion with our advisors and more brainstorming/research - it was time to detail the project more and begin to set official documentation.

As part of this project was a study of the effects the game’s design would have on players, it was important ot try and base our decisions in research. The presentation below shows one of the presentations used to show how research was shaping our game’s idea. Which then was followed with the story beats!

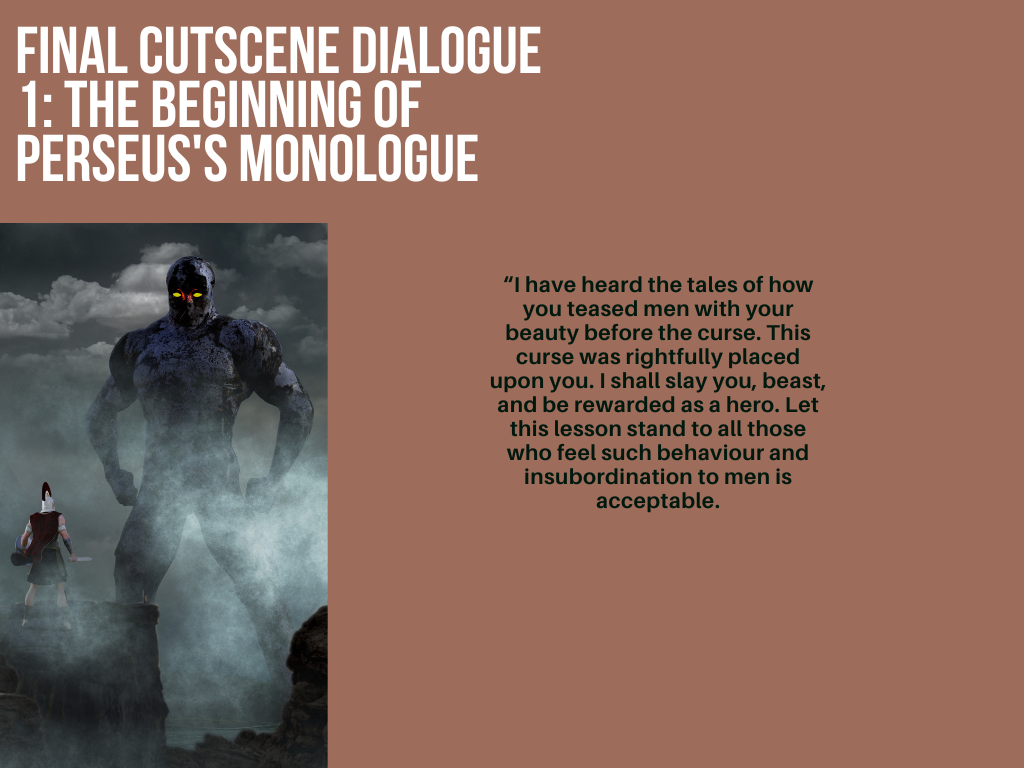

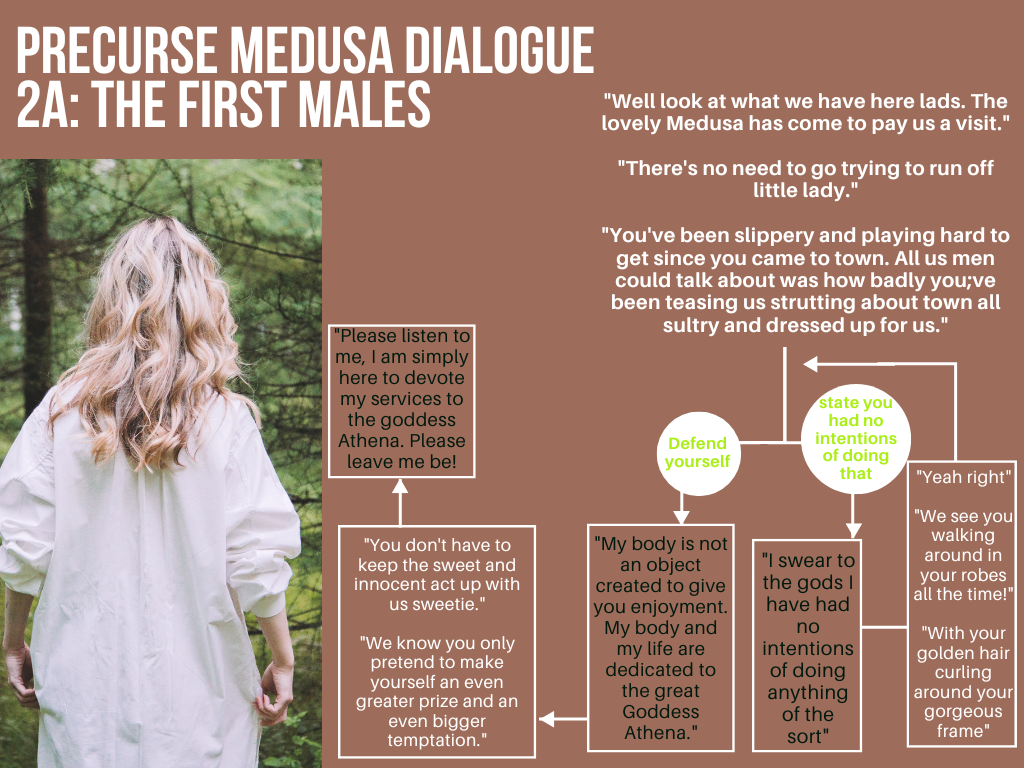

Because our game is supposed to foster empathy, we decided to incorporate perspective-taking in our design. In order to counteract some of the challenges that come with perspective-taking, we chose to first put the player in a common position. By having the player first play as Perseus, they are in a familiar perspective: that of the typical male hero, a character that exhibits the stereotypically masculine traits of strength, arrogance, and a distinct lack of empathy.

Partway through the game, we then shift the game’s perspective to that of Medusa, with the hopes that having the player take Medusa’s perspective will increase the level at which players empathize with the character, as well as lower rape myth acceptance values (as the player will experience a sexual assault survivor’s perspective).

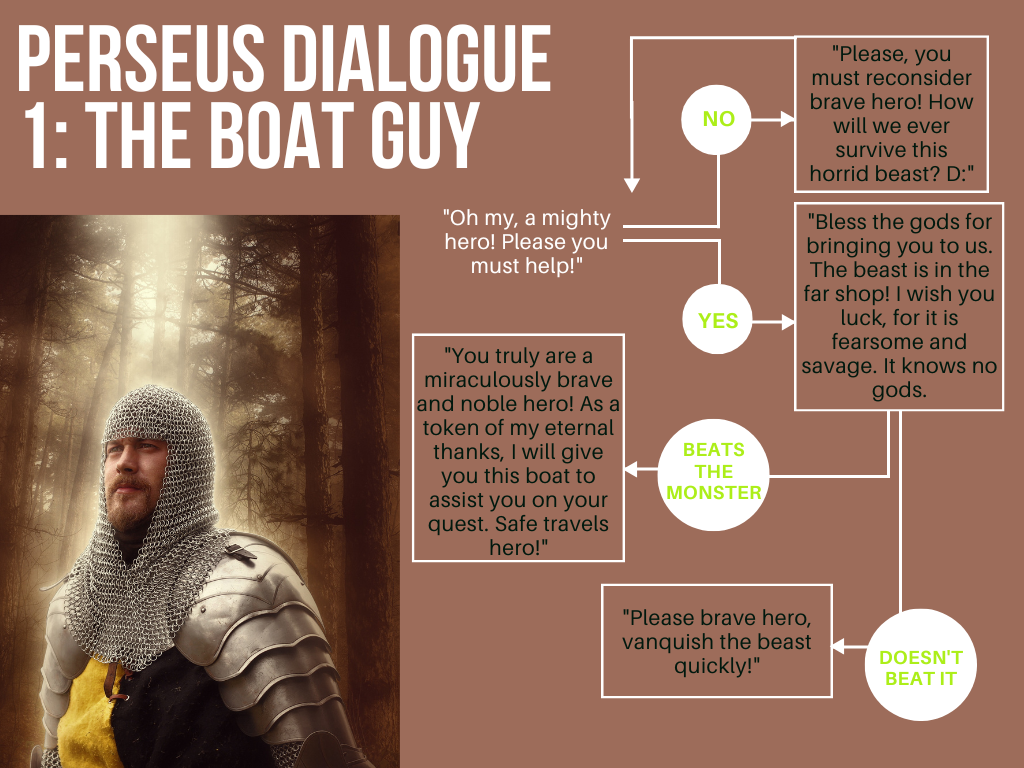

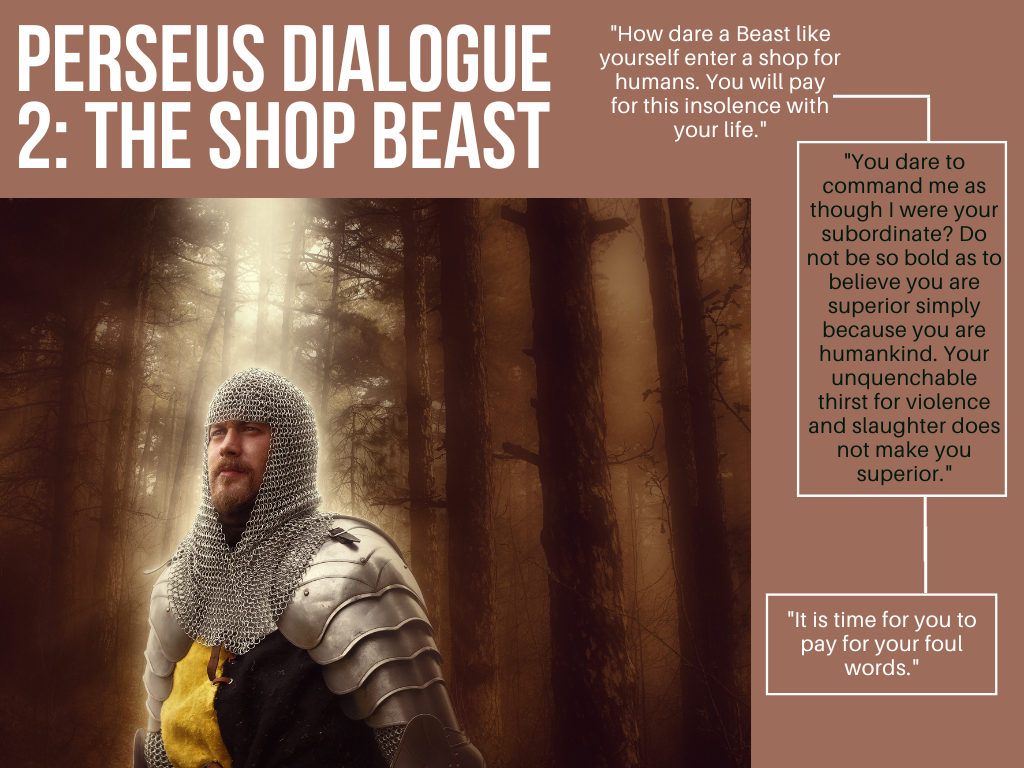

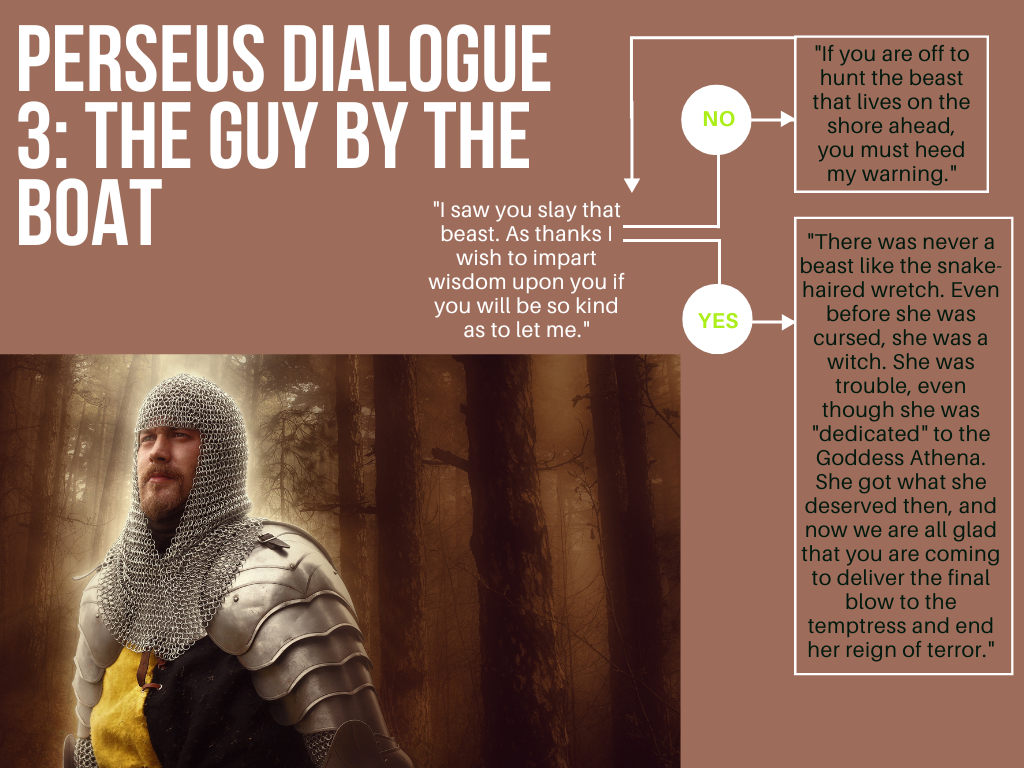

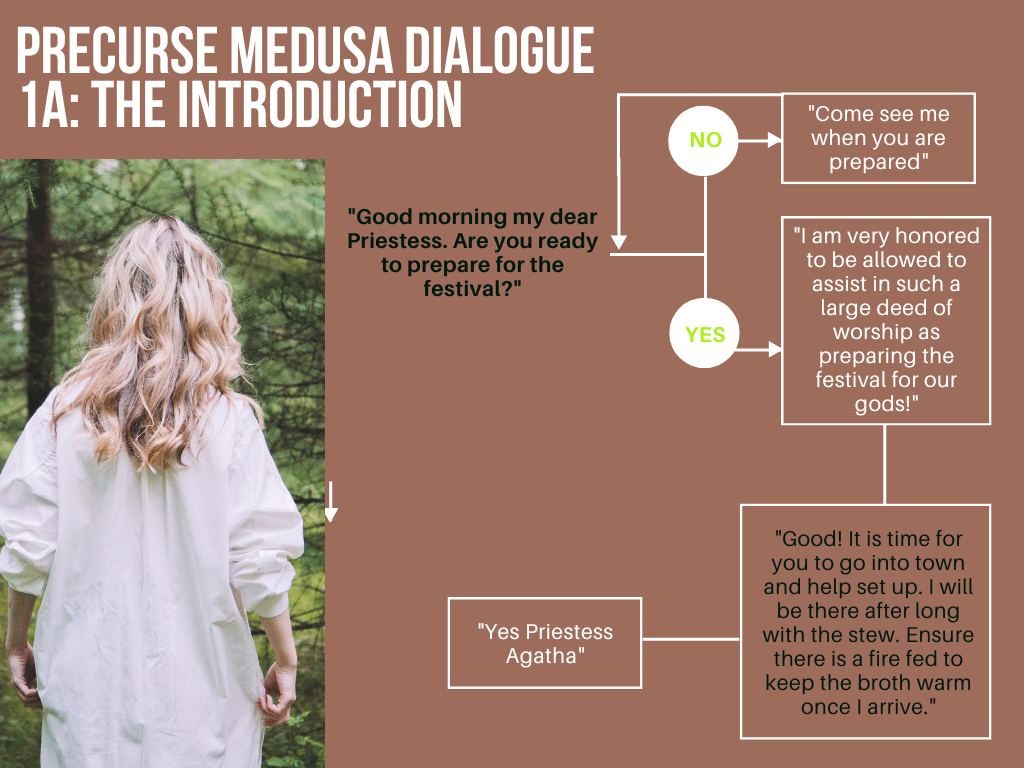

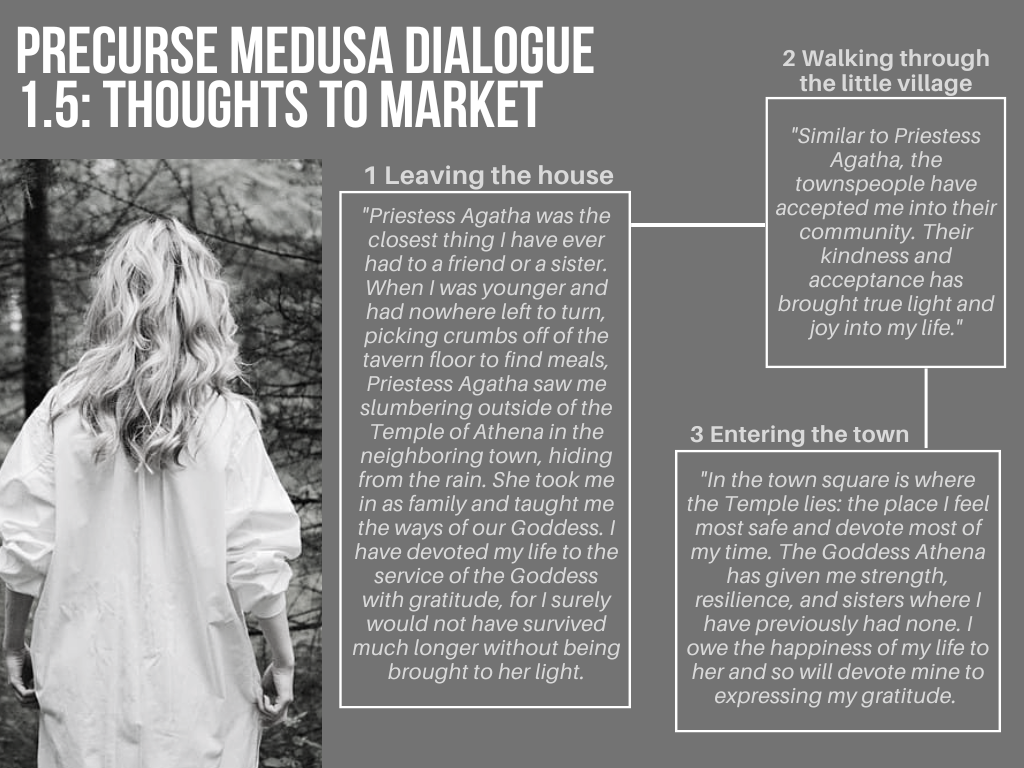

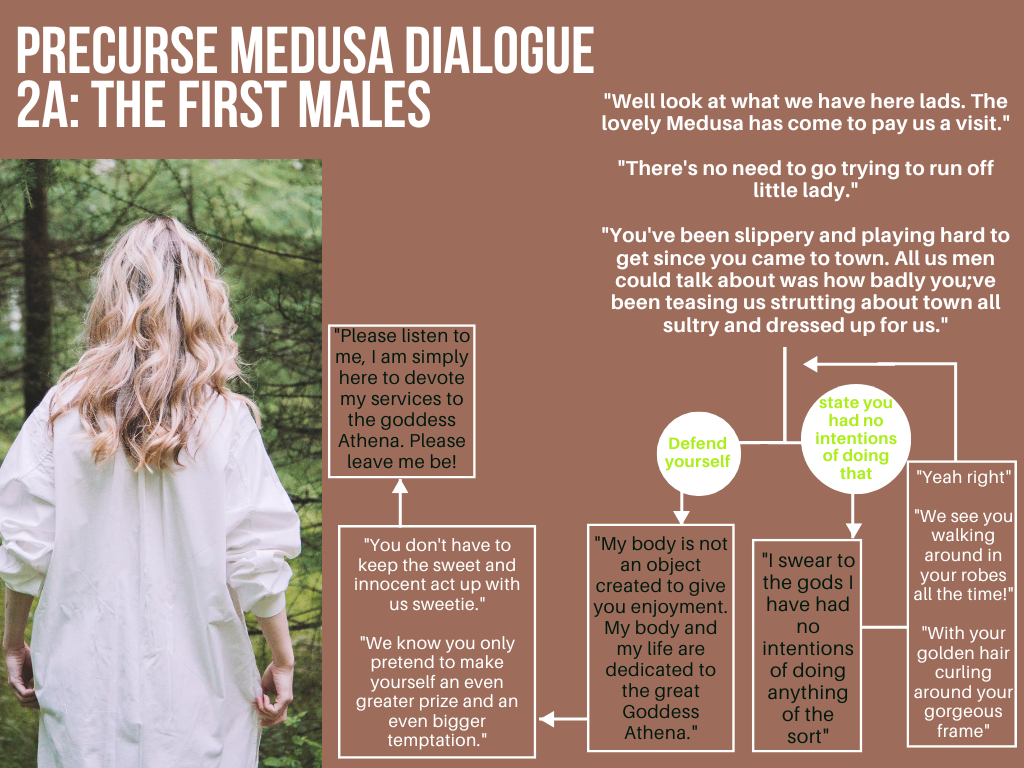

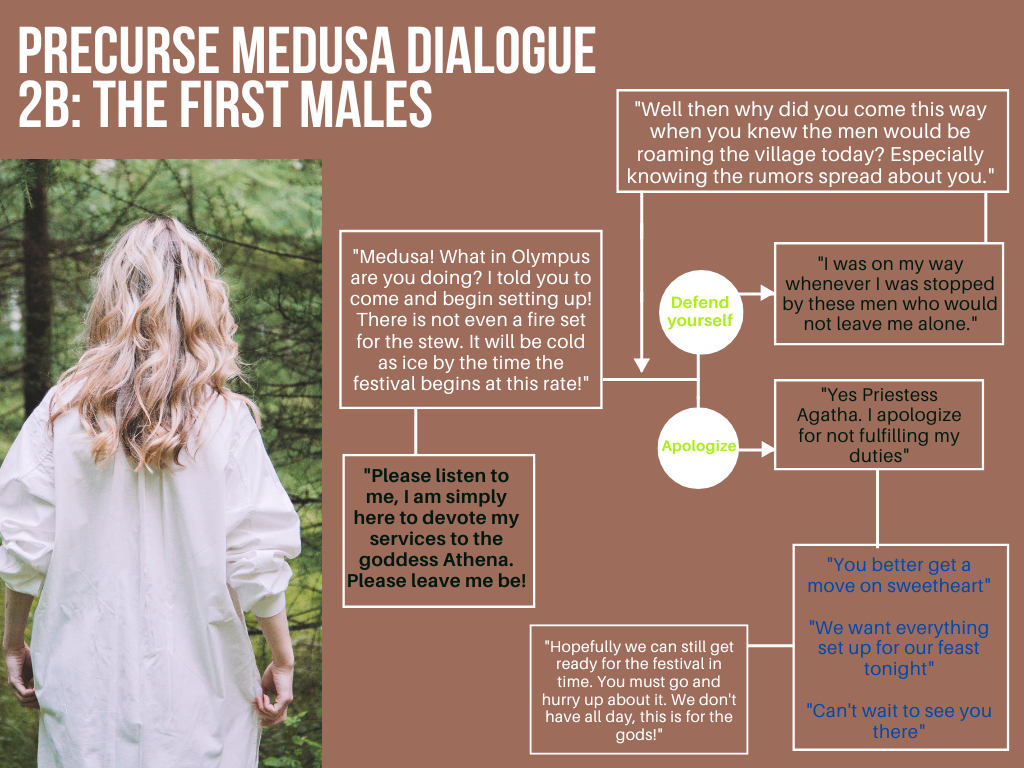

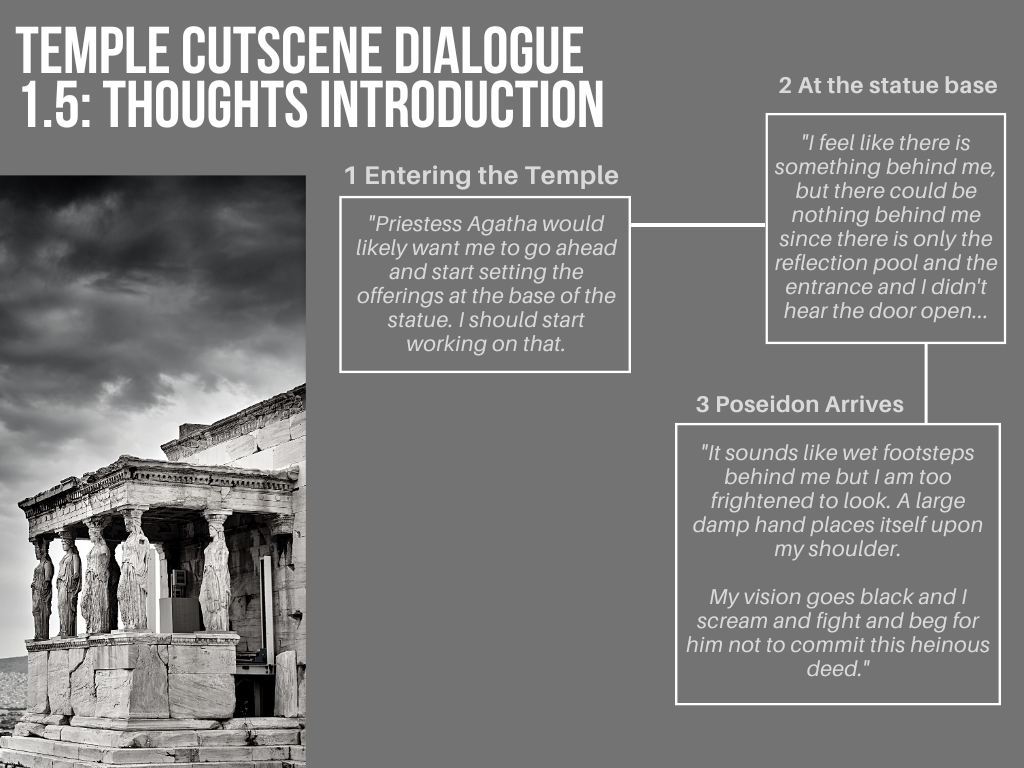

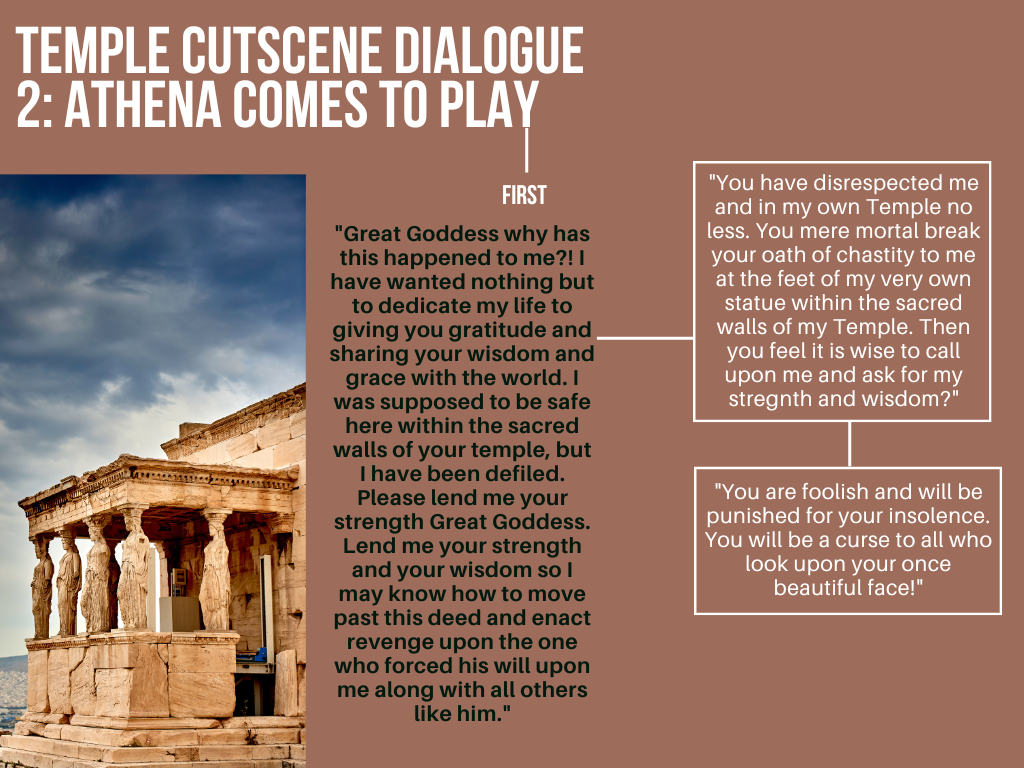

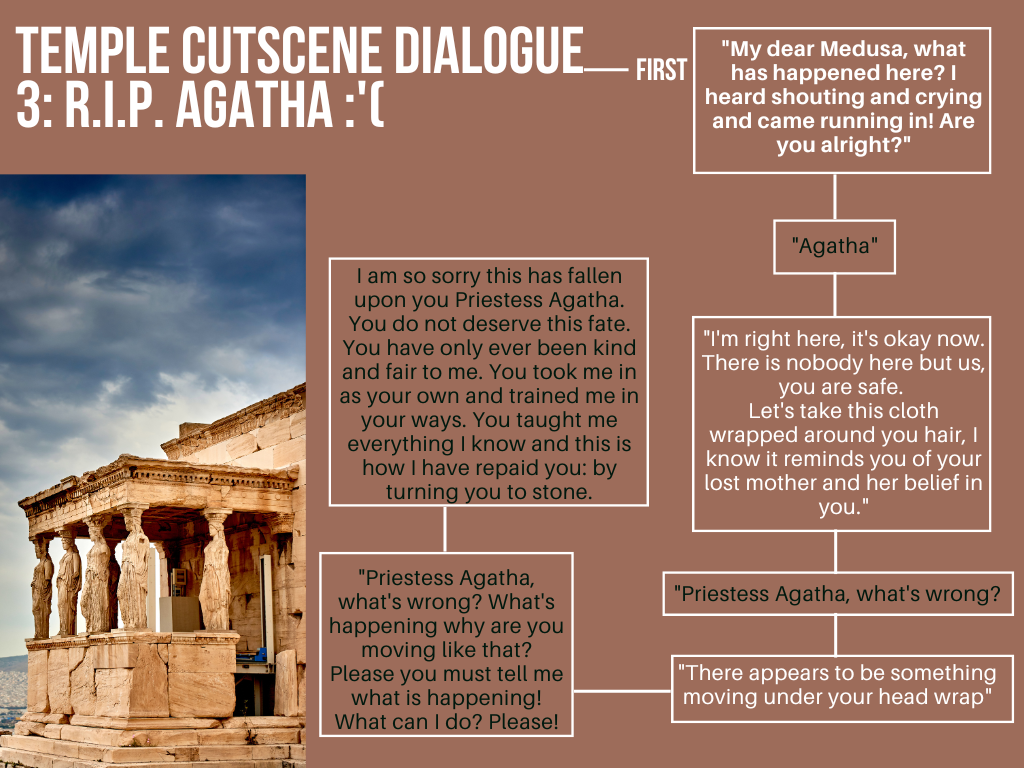

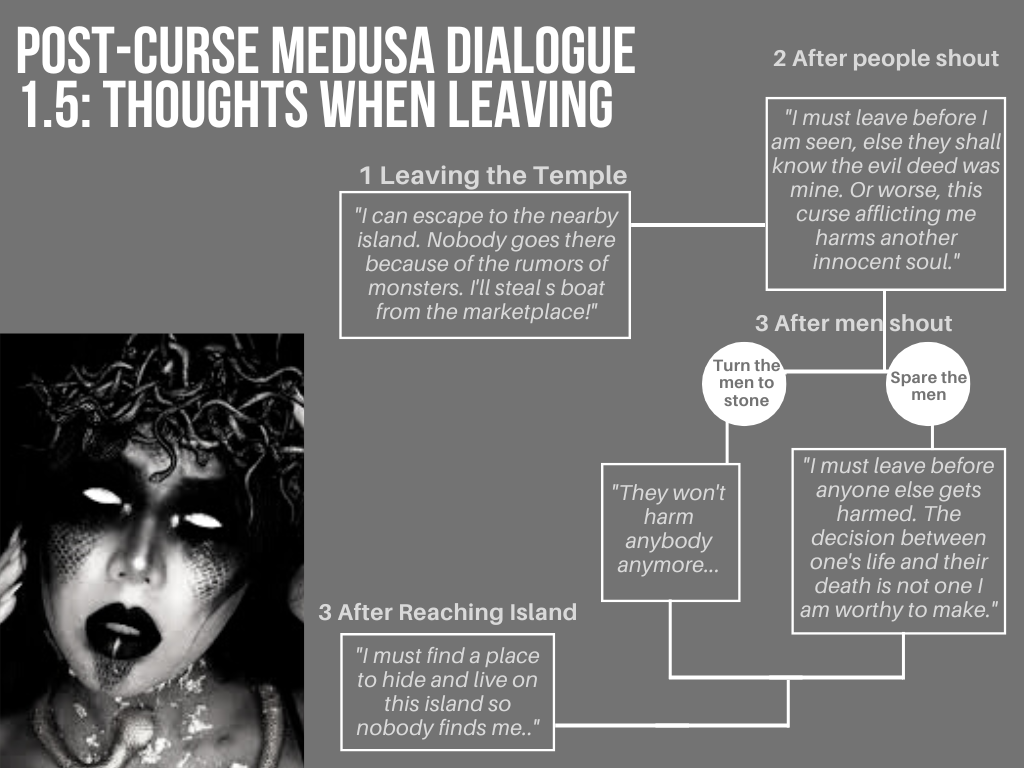

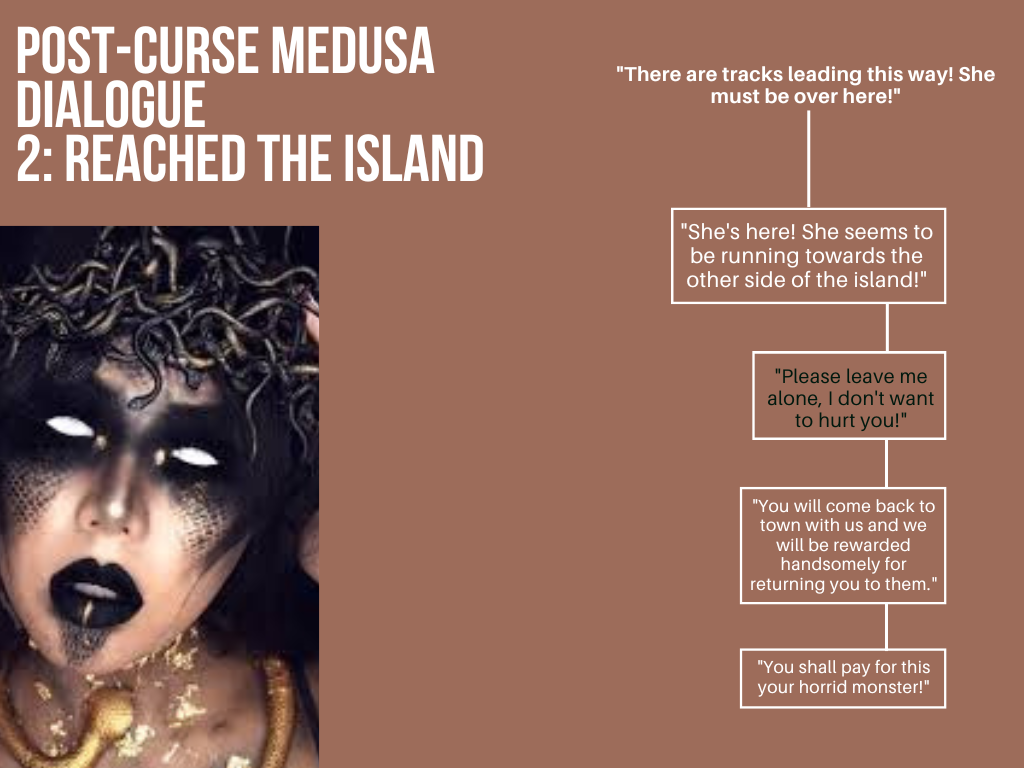

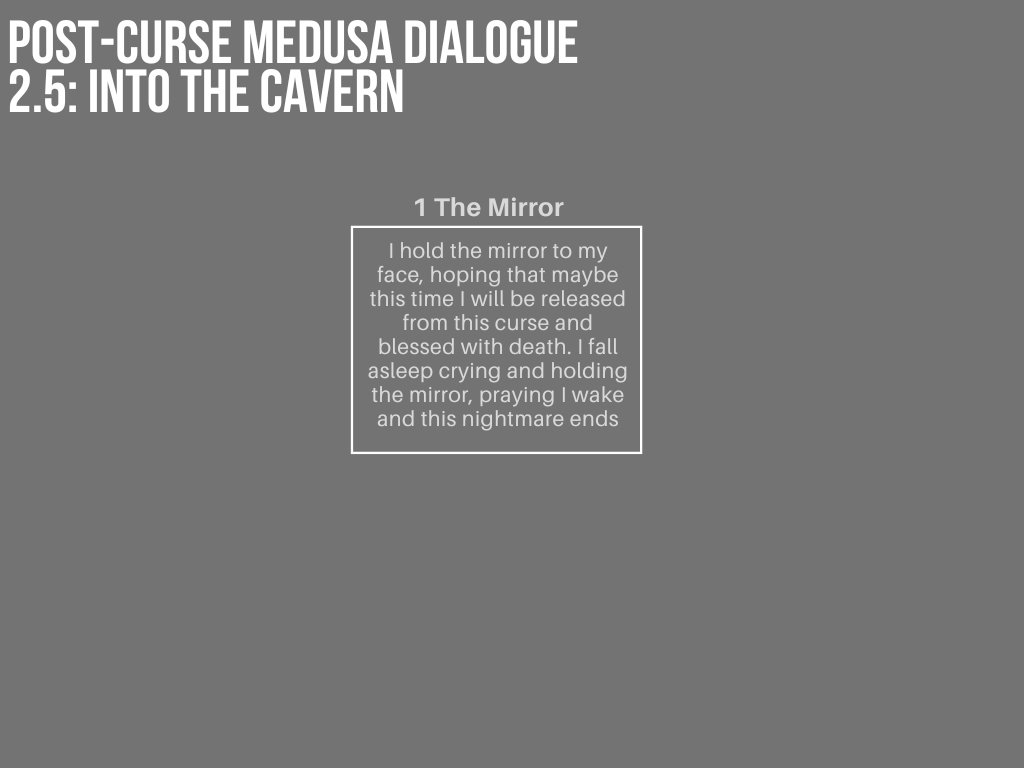

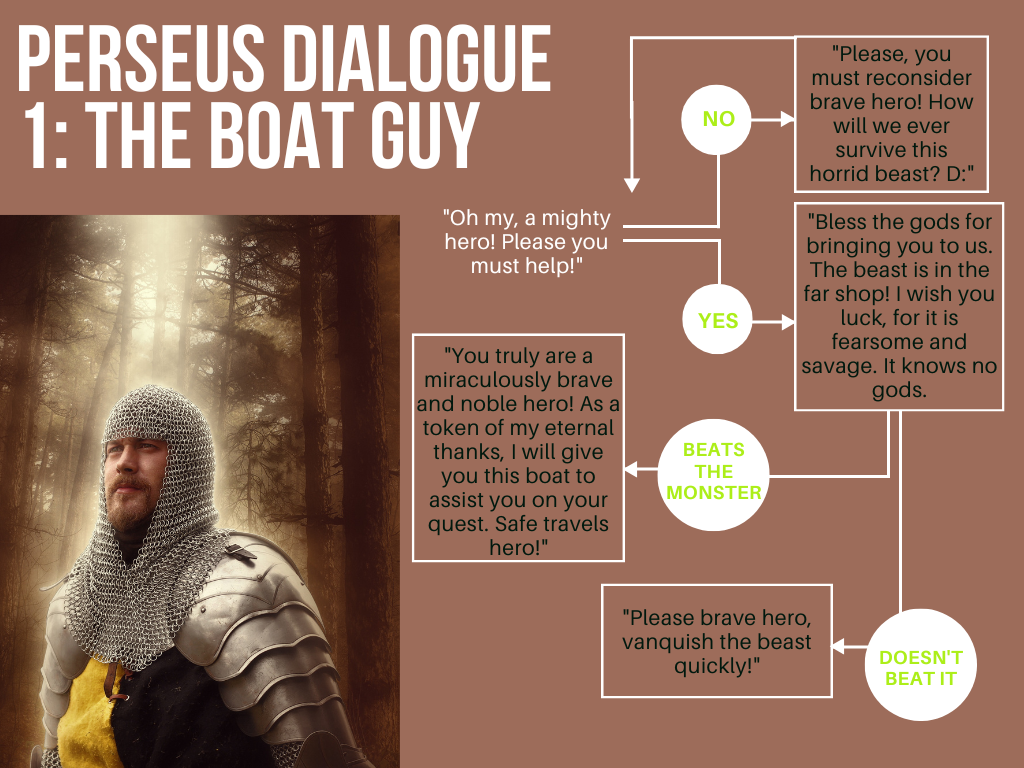

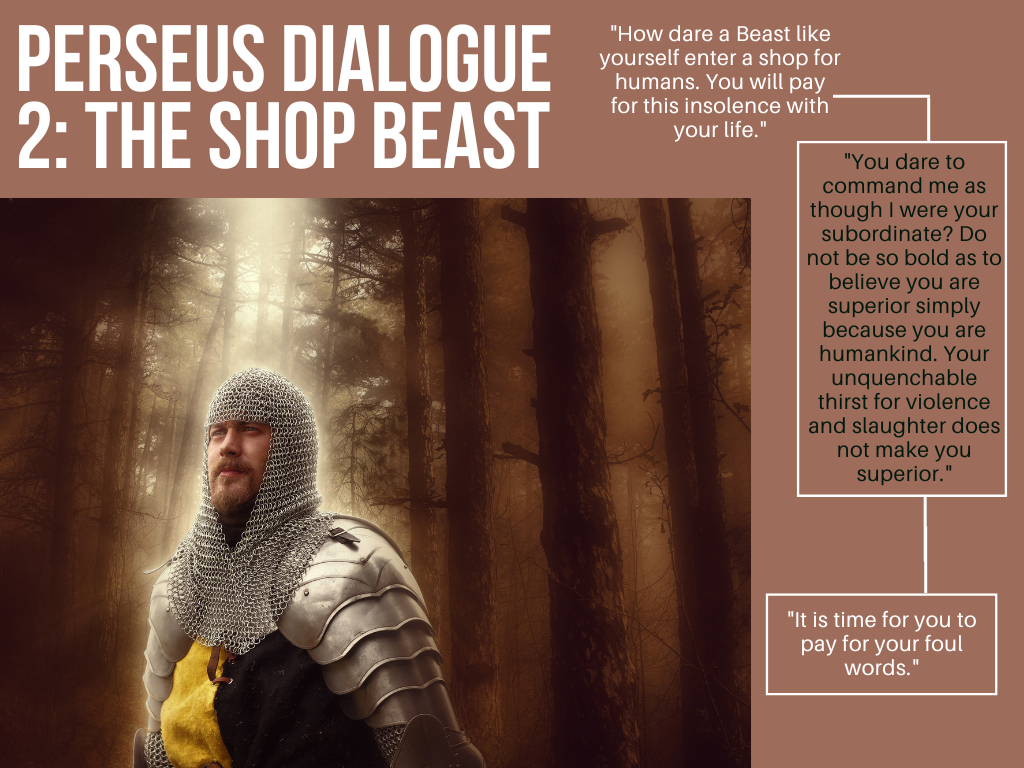

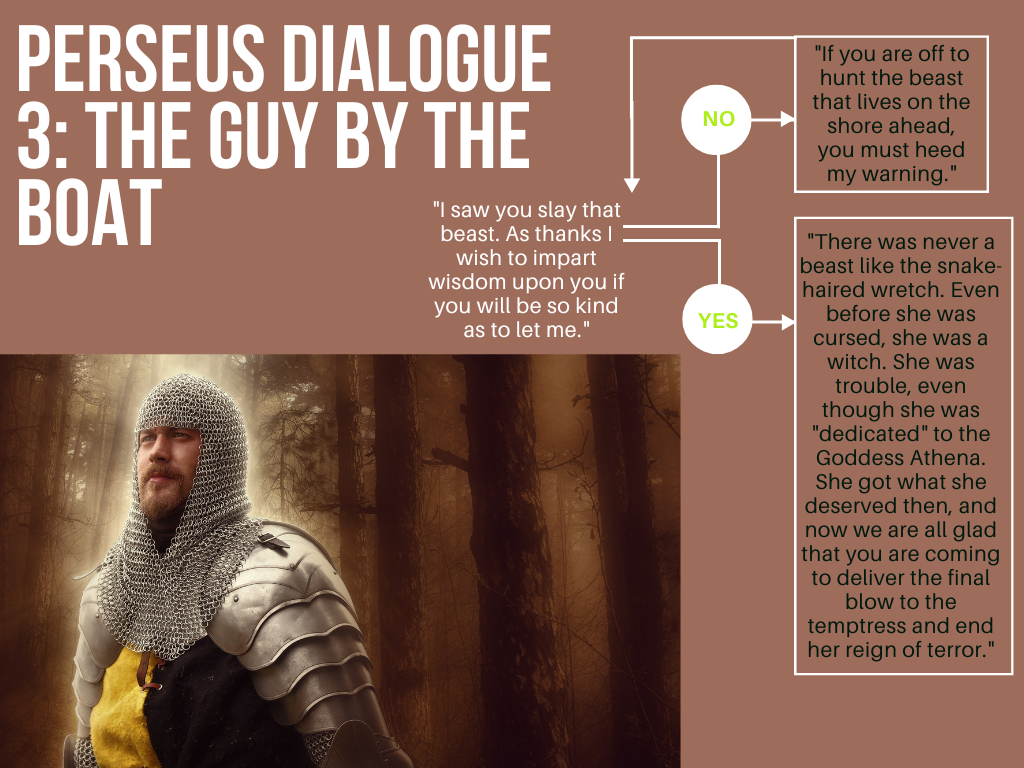

I then worked out an overall story draft for the game and worked on turning that into dialogue flow charts for easier implementation. The flow charts (or dialogue trees) were accompanied by a document detailing resoning behind the dialogue choices as well as a document to gather feedback for future revisions.

The full collection of original dialogue trees can be found in this section below

The team began really focusing on the game creation and we all spent a lot of time reviewing the pacing of the dialogue, any awkwardness and began preparing updates to match scope.

You can watch an early version of our Medusa transformation cutscene below

We wanted to reflect the psychological effects of sexual assault on the victims within the game. There are 11 themes that represent the layers of trauma on an assault victim (Lebowitz & Wigren, 2005).

In order to craft a believable narrative and appropriately represent the story of an assault survivor, we worked on incorporating these themes into our story and our game as a whole.

We represented the fear, helplessness, and freeze response that victims often feel during the scene where Medusa is assaulted by Poseidon (shown in the clip above).

We decided to remove the control from the player, only allowing them to advance the dialogue. This forced the player to experience being helpless and facing a situation they had no control over, along with whatever repercussions it may come with.

The biological response named the “Freeze” response occurs when the likelihood of escaping danger seems nonexistent. Freezing often leads victims to dissociate during (and after) the violence being acted upon them (Lebowitz & Wigren, 2005, p. 4). This was represented by having the scene fade out (an abstract representation of disassociation caused by the freeze response). After becoming conscious once more, Medusa reaches out to the powerful figure she trusts, Athena, for help but is only blamed for what happened and punished, resembling the reality many victims of sexual assault suffer from today.

We designed the ending of our game to ensure that players made a connection between the themes within it and our society today. To this end, we took clippings of news articles with headlines referencing r*pe and stitched them into a video (seen in the video below). These articles were meant to symbolize the prevalence and awareness of rape within our society, as can be seen in the speed at which they appear. They appear slowly at first, allowing the player to read the entire article headline and absorb the information between each appearance. The articles then began to fade in faster, covering the other ones already on screen. Eventually the articles appeared so rapidly that the player would not be able to read them all, overwhelming them. Once the screen was completely covered, the articles all faded out, to be replaced with a single line of text: “The devastating effects of rape and the dismissal of survivors’ realities has carried on for centuries and is still alive and thriving today”.

This sentence reinforced the connection between our game and the real world, making it nearly impossible to miss. Over all the articles, somber piano music played, along with a team member reading quotes from sexual assault survivors. The quotes were included to provide more context about how devastating sexual assault can be to survivors, and was paired with the piano music to make the video more emotional. While we were initially concerned that the combination of music and voice would overwhelm the players, a brief pre-testing suggested otherwise. The music and quotes lasted until all the articles faded out, leaving the players to reflect in solemn silence as the sentence appeared, followed by credits for the music and quotes, before eventually being left with a black screen.

COMBAT/ENEMY AI

For our initial prototype the enemies had no animations and simply moved in a straight line towards the player. Once they collided with the player, the player died and the game reset.

While the project shifted many times over the course of development - I’m incredibly proud of this piece and the teammates who worked with me on it! I’m only further inspired to create pieces to try and make change and am glad to have had the chance to learn from the awesome advisors that guided us and the project and team itself!

Hide Designer Details

Our first goal was to update the movement logic for the AI so they move around the environment rather than directly over all of the trees. Unity has a built-in feature for 3D games where it can automatically create NavMesh. Unfortunately, our game was in 2D, so we weren't able to use that feature without a little help.

Our lead programmer, Tyler Sprowl, found a software called NavMeshPlus that allowed us to use Unity's built-in NavMesh feature for our enemies. After adding in some specific lines of code, we now had the enemies move towards the player in a new and improved tree-aware way.

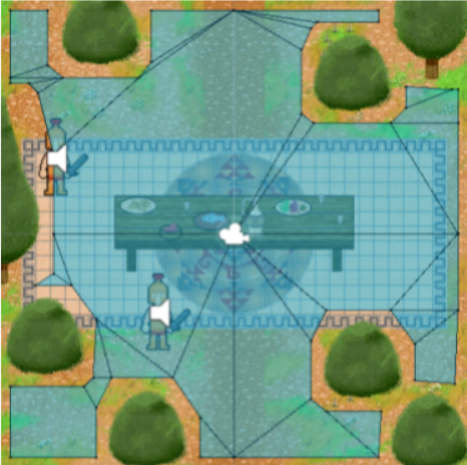

Here is a screenshot that shows an example of this NavMesh. Note the blue area, which signifies where the enemy can move. In instances where it is smaller than the enemy, it does not pass through there.

Next was combat, and we needed our enemies to be able to visibly attack. We created attack boxes for the enemies which were invisible shapes that, when colliding with the player, caused them to play an animation and "die".

However, the attack box couldn’t always be active. This was fixed by simply having the script check to see if the enemy was attacking, which would then cause the attack box to activate It would then deactivate once the attack animation had finished

A report of the game development, psychology studies, and research results can be found in the link below.